5 Curriculum Design, Development and Models: Planning for Student Learning

“. . . there is always a need for newly formulated curriculum models that address contemporary circumstance and valued educational aspirations.” –Edmond Short

Introduction

Curriculum design refers to the structure or organization of the curriculum, and curriculum development includes the planning, implementation, and evaluation processes of the curriculum. Curriculum models guide these processes.

Essential Questions

- What is curriculum design?

- What questions did Tyler pose for guiding the curriculum design process?

- What are the major curriculum design models?

- What unique element did Goodlad add to his model?

- In addition to the needs of the learner, what did Hilda Taba add to her model?

Meaning of Curriculum Design

From Curriculum Studies, pp. 65-68

Curriculum design is largely concerned with issues such as what to include in the curriculum and how to present it in such a way that the curriculum can be implemented with understanding and success (Barlow et al., 1984). Therefore, curriculum design refers to how the components of the curriculum have been arranged in order to facilitate learning (Shiundu & Omulando, 1992).

Curriculum design is concerned with issues of choosing what the organizational basis or structural framework of the curriculum is. The choice of a design often implies a value position.

As with other curriculum-related concepts, curriculum design has a variety of definitions, depending on the scholars involved. For example, Doll (1992) says that curriculum design is a way of organizing that permits curriculum ideas to function. She also adds that curriculum design refers to the structure or pattern of the organization of the curriculum.

The curriculum design process results in a curriculum document that contains the following:

- a statement of purpose(s),

- an instructional guide that displays behavioral objectives and content organization in harmony with school organization,

- a set of guidelines (or rules) governing the use of the curriculum, and

- an evaluation plan.

Thus, curriculum is designed to fit the organizational pattern of the school/institution for which it is intended.

How a curriculum is conceptualized, organized, developed, and implemented depends on a particular state’s or district’s educational objectives. Whatever design is adopted depends also on the philosophy of education.

There are several ways of designing school curriculum. These include subject-centered, learner-centered, integrated, or broad fields (which combines two or more related subjects into one field of study; e.g., language arts combine the separate but related subjects of reading, writing, speaking, listening, comprehension, and spelling into a core curriculum).

Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

This curriculum design refers to the organization of curriculum in terms of separate subjects, e.g., geography, math, and history, etc. This has been the oldest school curriculum design and the most common in the world. It was even practiced by the ancient Greek educators. The subject-centered design was adapted by many European and African countries as well as states and districts in the United States. An examination of the subject-centered curriculum design shows that it is used mainly in the upper elementary and secondary schools and colleges. Frequently, laypeople, educators, and other professionals who support this design received their schooling or professional training in this type of system. Teachers, for instance, are trained and specialized to teach one or two subjects at the secondary and sometimes the elementary school levels.

There are advantages and disadvantages of this approach to curriculum organization. There are reasons why some educators advocate for it while others criticize this approach.

Advantages of Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

It is possible and desirable to determine in advance what all children will learn in various subjects and grade levels. For instance, curricula for schools in centralized systems of education are generally developed and approved centrally by a governing body in the education body for a given district or state. In the U.S., the state government often oversees this process which is guided by standards.

- It is usually required to set minimum standards of performance and achievement for the knowledge specified in the subject area.

- Almost all textbooks and support materials on the educational market are organized by subject, although the alignment of the text contents and the standards are often open for debate.

- Tradition seems to give this design greater support. People have become familiar and more comfortable with the subject-centered curriculum and view it as part of the system of the school and education as a whole.

- The subject-centered curriculum is better understood by teachers because their training was based on this method, i.e., specialization.

- Advocates of the subject-centered design have argued that the intellectual powers of individual learners can develop through this approach.

- Curriculum planning is easier and simpler in the subject-centered curriculum design.

Disadvantages of Subject-Centered Curriculum Design

Critics of subject-centered curriculum design have strongly advocated a shift from it. These criticisms are based on the following arguments:

- Subject-centered curriculum tends to bring about a high degree of fragmentation of knowledge.

- Subject-centered curriculum lacks integration of content. Learning in most cases tends to be compartmentalized. Subjects or knowledge are broken down into smaller seemingly unrelated bits of information to be learned.

- This design stresses content and tends to neglect the needs, interests, and experiences of the students.

- There has always been an assumption that information learned through the subject-matter curriculum will be transferred for use in everyday life situations. This claim has been questioned by many scholars who argue that the automatic transfer of the information already learned does not always occur.

Given the arguments for and against subject-centered curriculum design, let us consider the learner-centered or personalized curriculum design.

Learner-Centered/Personalized Curriculum Design

Learner-centered curriculum design may take various forms such as individualized or personalized learning. In this design, the curriculum is organized around the needs, interests, abilities, and aspirations of students.

Advocates of the design emphasize that attention is paid to what is known about human growth, development, and learning. Planning this type of curriculum is done along with the students after identifying their varied concerns, interests, and priorities and then developing appropriate topics as per the issues raised.

This type of design requires a lot of resources and manpower to meet a variety of needs. Hence, the design is more commonly used in the U.S. and other western countries, while in the developing world the use is more limited.

To support this approach, Hilda Taba (1962) stated, “Children like best those things that are attached to solving actual problems that help them in meeting real needs or that connect with some active interest. Learning in its true sense is an active transaction.”

Advantages of the Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

- The needs and interests of students are considered in the selection and organization of content.

- Because the needs and interests of students are considered in the planning of students’ work, the resulting curriculum is relevant to the student’s world.

- The design allows students to be active and acquire skills and procedures that apply to the outside world.

Disadvantages of the Learner-Centered Curriculum Design

- The needs and interests of students may not be valid or long lasting. They are often short-lived.

- The interests and needs of students may not reflect specific areas of knowledge that could be essential for successful functioning in society. Quite often, the needs and interests of students have been emphasized and not those that are important for society in general.

- The nature of the education systems and society in many countries may not permit learner-centered curriculum design to be implemented effectively.

- As pointed out earlier, the design is expensive in regard to resources, both human and fiscal, that are needed to satisfy the needs and interests of individual students.

- This design is sometimes accused of shallowness. It is argued that critical analysis and in-depth coverage of subject content is inhibited by the fact that students’ needs and interests guide the planning process.

Broad Fields/Integrated Curriculum

From Curriculum Studies, pp. 69-80

In the broad fields/integrated curriculum design, two, three, or more subjects are unified into one broad course of study. This organization is a system of combining and regrouping subjects that are related to the curriculum.

This approach attempts to develop some kind of synthesis or unity for the entire branch or more branches of knowledge into new fields.

Examples of Broad Fields

- Language Arts: Incorporates reading, writing, grammar, literature, speech, drama, and international languages.

- General Science: Includes natural and physical sciences, physics, chemistry, geology, astronomy, physical geography, zoology, botany, biology, and physiology

- Other: Include environmental education and family-life education

Advocates of the broad fields/integrated designs believe that the approach brings about unification and integration of knowledge. However, looking at the trend of events in curriculum practice in many states and countries, this may not have materialized effectively. The main reason is that teachers are usually trained in two subjects at the university level, thus making it difficult for them to integrate more areas than that. For instance, general science might require physics, chemistry, biology, and geology, but science teachers may have only studied two of these areas in depth.

Advantages of Broad Field/Integrated Curriculum Design

- It is based on separate subjects, so it provides for an orderly and systematic exposure to the cultural heritage.

- It integrates separate subjects into a single course; this enables learners to see the relationships among various elements in the curriculum.

- It saves time in the school schedule.

Disadvantages of Broad Field/Integrated Curriculum Design

- It lacks depth and cultivates shallowness.

- It provides only bits and pieces of information from a variety of subjects.

- It does not account for the psychological organization by which learning takes place.

Core Curriculum Design

Meaning of Core Curriculum

The concept core curriculum is used to refer to areas of study in the school curriculum or any educational program that is required by all students. The core curriculum provides students with “common learning” or general education that is considered necessary for all. Thus, the core curriculum constitutes the segment of the curriculum that teaches concepts, skills, and attitudes needed by all individuals to function effectively within the society.

Characteristics of Core Curriculum Design

The basic features of the core curriculum designs include the following:

- They constitute a section of the curriculum that all students are required to take.

- They unify or fuse subject matter, especially in subjects such as English, social studies, etc.

- Their content is planned around problems that cut across the disciplines. In this approach, the basic method of learning is problem-solving using all applicable subject matter.

- They are organized into blocks of time, e.g. two or three periods under a core teacher. Other teachers may be utilized where it is possible.

Types of Core Curriculum Designs

The following types of core curriculum are commonly found in secondary schools and college curriculums.

Type One

Separate subjects taught separately with little or no effort to relate them to each other (e.g., mathematics, science, languages, and humanities may be taught as unrelated core subjects in high schools).

Type Two

The integrated or “fused” core design is based on the overall integration of two or more subjects, for example:

- Physics, chemistry, biology, and zoology may be taught as general science.

- Environmental education is an area with an interdisciplinary approach in curriculum planning.

- History, economics, civics, and geography may be combined and taught as social studies.

Curriculum Design Models

There are a variety of curriculum design models to guide the process. Most of the designs are based on Ralph Tyler’s work which emphasizes the role and place of objectives in curriculum design.

Ralph Tyler’s Model

Tyler’s Model (1949) is based on the following four (4) fundamental questions he posed for guiding the curriculum design process. They are as follows:

- What educational purposes is the school seeking to attain?

- What educational experiences are potentially provided that are likely to attain these purposes?

- How can these educational experiences be effectively organized?

- How can we determine whether these purposes are being attained?

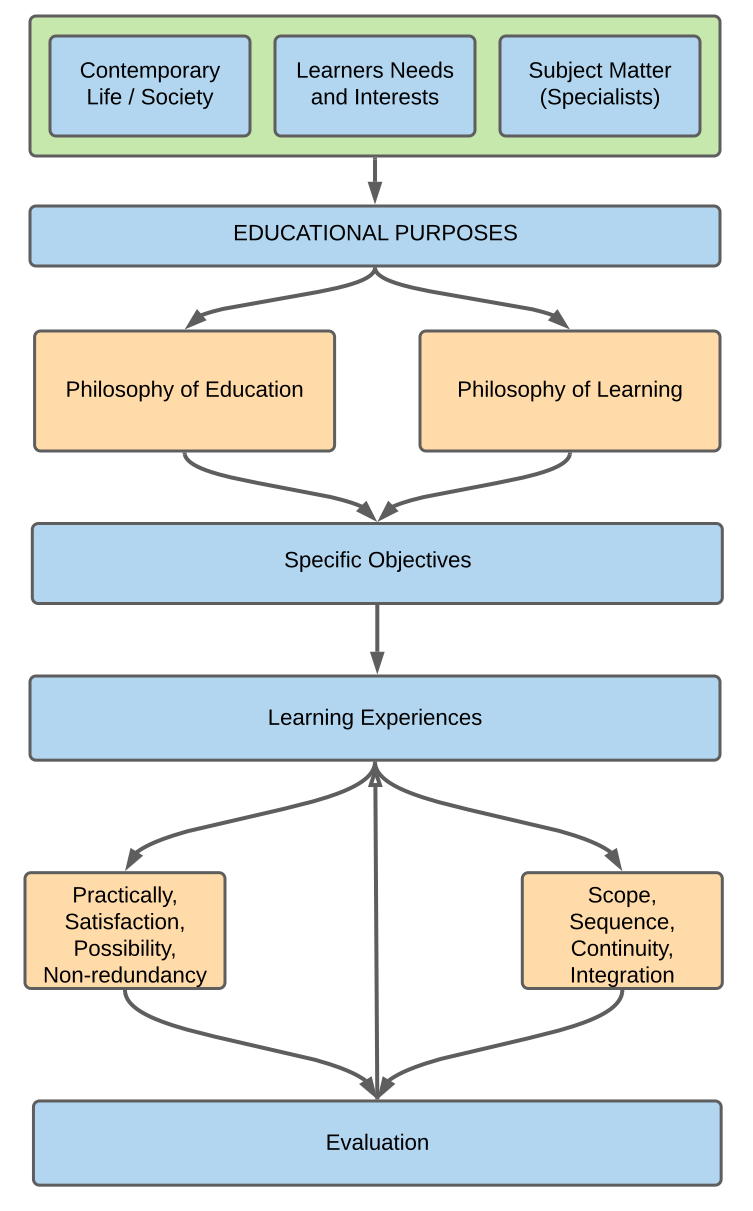

Schematically, Tyler’s model is presented as follows.

Application of Ralph Tyler’s Model in Curriculum Design

In applying Tyler’s model to curriculum design, the process begins with framing objectives for the curriculum. Because of its emphasis on the importance of objectives, it is considered an objective-based model. This process starts with analyzing information from various data sources. Data sources for curriculum according to Tyler include:

- Contemporary society/life

- For this source, the designer analyzes the issues affecting society that could be solved through education.

- Examples are cultural issues, socio-economic issues, and health issues such as HIV/AIDS among.

- Learner’s needs and interests

- Subject specialists/subject matter

From these sources, the designer develops general objectives. These are subjected to a screening process, using the philosophy of education and psychology of learning as the major screens. Social values are also used as a screen, but sometimes these are subsumed in the philosophy of education. This yields a feasible number of objectives that are focused on in education.

Specific objectives are then derived from the general objectives. For each of the specific objectives, learning experiences are identified. In this context, the learning experiences include the subject matter/content and learning activities.

The next step is the organization of learning experiences. This is done to ensure effective learning takes place. The various principles of the organization include scope, sequence, integration, and continuity, among others. The final step involves evaluation, to determine the extent to which the objectives have been met.

Feedback from the evaluation is then used to modify the learning experiences and the entire curriculum as found necessary.

Learning Experiences

Learning experiences refer to the interaction between the learner and the external conditions in the environment which they encounter. Learning takes place through the active participation of the students; it is what the students are involved in that they learn, not what the teacher does.

The problem of selecting learning experiences is the problem of determining the kind of experiences likely to produce given educational objectives and also the problem of how to set up opportunity situations that evoke or provide within the student the kinds of learning experiences desired.

General Principles in Selecting Learning Experiences

- Provide experiences that give students opportunities to practice the behavior and deal with the content implied.

- Provide experiences that give satisfaction from carrying on the kind of behavior implied in the objectives.

- Provide experiences that are appropriate to the student’s present attainments, his/her predispositions.

- Keep in mind that many experiences can be used to attain the same educational objectives.

- Remember that the same learning experience will usually bring about several outcomes.

Selection of Subject Matter/Content

The term subject matter/content refers to the data, concepts, generalizations, and principles of school subjects such as mathematics, biology, or chemistry that are organized into bodies of knowledge sometimes called disciplines. For instance, Ryman (1973) specifically defines content as:

Knowledge such as facts, explanations, principles, definitions, skills, and processes such as reading, writing, calculating, dancing, and values such as the beliefs about matters concerned with good and bad, right and wrong, beautiful and ugly.

The selection of content and learning experiences is one crucial part of curriculum making. This is mainly because of the explosion of knowledge that made the simplicity of school subjects impossible. As specialized knowledge increases, it is necessary either to add more subjects or to assign new priorities in the current offerings to make room for new knowledge and new concepts.

New requirements for what constitute literacy have also emerged. In secondary schools, the usual method of accommodating new demands is to introduce new subjects or to put new units into existing subjects.

Improved educational technology such as the use of television, radio, computers, and multi-media resources support an expansion of what can be learned in a given period. New technological aids for self- teaching, for communicating information, and for learning a variety of skills are shifting the balance of time and effort needed for acquiring a substantial portion of the curriculum. What then are the criteria for the selection of content?

Criteria for the Selection of Content

Several criteria need to be considered in selecting content. These include the validity, significance, needs, and interests of learners.

Validity

The term validity implies a close connection between content and the goals which it is intended to serve. In this sense, content is valid if it promotes the outcomes that it is intended to promote. In other words, does the curriculum include concepts and learnings that it states it does?

Significance

The significance of curriculum content refers to the sustainability of the material chosen to meet certain needs and ability levels of the learners.

Needs and Interests of the Learner

The needs and interests of the learners are considered in the selection of content to ensure a relevant curriculum to the student’s world. This also ensures that the students will be more motivated to engage with the curriculum.

Utility

In this context, the subject matter of a curriculum is selected in the light of its usefulness to the learner in solving his/her problems now and in the future.

Learnability

Curriculum content is learnable and adaptable to the students’ experiences. One factor in learnability is the adjustment of the curriculum content and the focus of learning experiences on the abilities of the learners. For effective learning, the abilities of students must be taken into account at every point of the selection and organization.

Consistency with Social Realities

If the curriculum is to be a useful prescription for learning, its content, and the outcomes it pursues need to be in tune with the social and cultural realities of the culture and the times.

John Goodlad’s Model

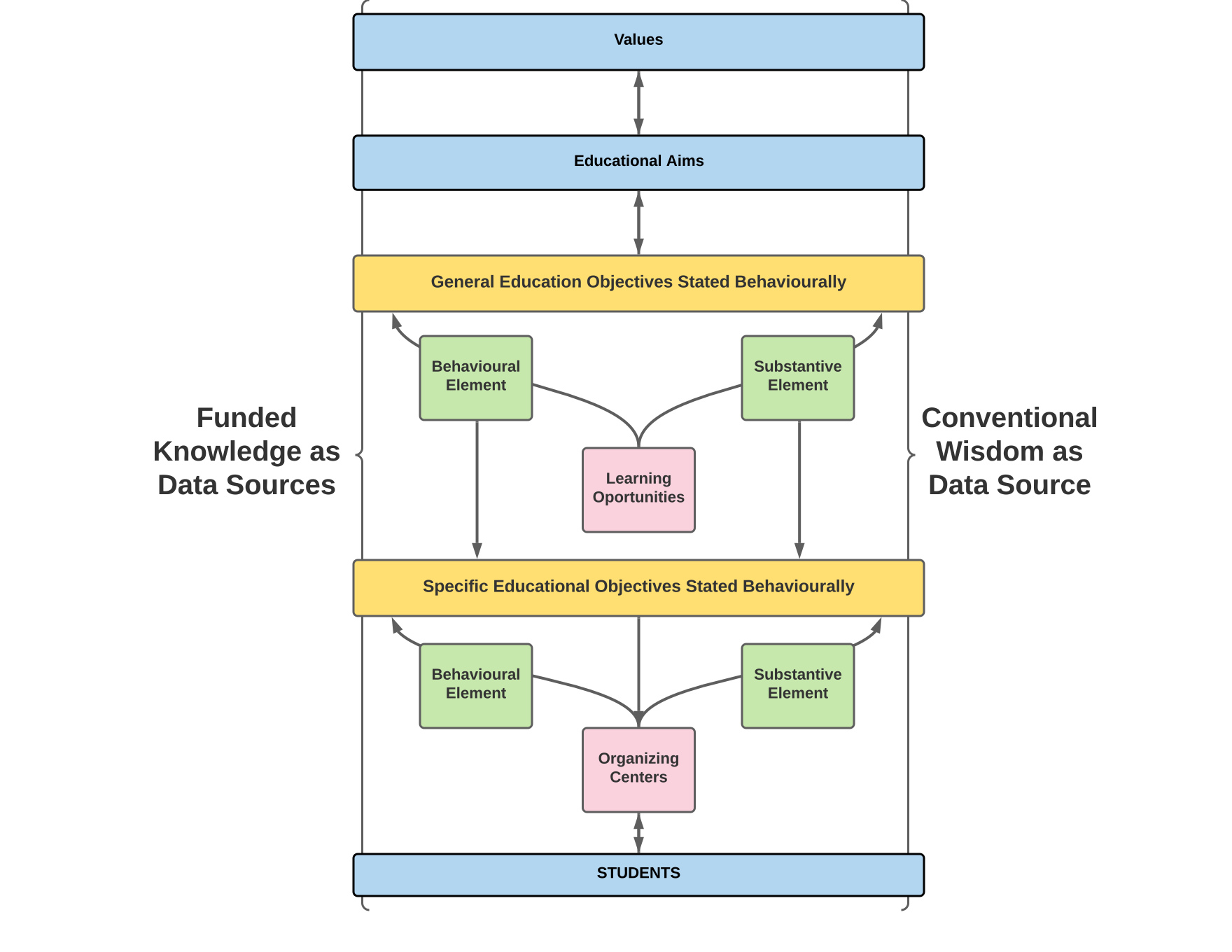

The Goodlad model deviates a bit from the Ralph Tyler’s model. It is particularly unique in its use of social values. Whereas Tyler considers them as a screen, Goodlad proposes they are used as data sources. Hence, Goodlad proposes four data sources:

- values,

- funded knowledge,

- conventional wisdom, and

- student needs and interests.

Values

John Goodlad was a Canadian-born educator and author who believed that the most important focus of education should not be based on standardized testing, but rather to prepare young people to be well-informed citizens in democracy. His inclusion of values in the curriculum-development chart reflects his belief that educational systems must be driven by goals or values. He believed that education has a moral dimension, and those who teach are “moral agents.” To be a professional teacher means that one is a moral agent with a moral obligation, including initiating the young into a culture. In the United States, this means “critical enculturation into a political democracy” because a democratic society depends on the renewal and blending of self-interests and the public welfare (Goodlad, 1988). For that reason, Goodlad places “values” at the very top of his model.

Funded Knowledge

Funded knowledge is knowledge which is gained from research. Generally, research is heavily funded by various organizations. Information from research is used to inform educational practice in all aspects, particularly in curriculum design.

Conventional Wisdom

Conventional wisdom includes specialized knowledge within the society, for example from experts in various walks of life and ‘older’ people with life experiences. Students’ needs and interests are also considered in the design process.

Data from the various sources are then used to develop general aims of education from which general educational objectives are derived. These objectives are stated in behavioral terms. A behavioral objective has two components: a behavioral element and a substantive element. The behavioral element refers to the ‘action’ that a learner is able to perform, while the substantive element represents the ‘content’ or “substance” of the behavior.

From the general objectives, the curriculum designer identifies learning opportunities that facilitate the achievement of the general objectives. This could, for example, be specific courses of study.

The next step involves deriving specific educational objectives stated behaviorally. These are akin to instructional objectives. They are used to identify “organizing centers” which are specific learning opportunities, for example, a specific topic, a field trip, an experiment, etc.

Regarding evaluation, Goodlad proposed continuous evaluation at all stages of the design process. In the model, evaluation is represented by the double-edged arrows that appear throughout the model.

How then does Tyler’s model differ with that of John Goodlad’s?

Goodlad’s model departs from the traditional model based on Tyler’s work in several ways:

- recognition of references to scientific knowledge from research,

- use of explicit value statements as primary data sources,

- introduction of organizing centers i.e., the specific learning opportunities,

- continuous evaluation is used as a constant data source, not only as a final monitor of students’ progress (formative evaluation) but also for checking each step in the curriculum planning process. Hence, the model insists upon both formative and process evaluation.

Curriculum literature still has many more models for design. We shall highlight a few of them.

Other Curriculum Designs

There are many other curriculum design models developed by different scholars. Most of these models are objectives-based, i.e. they focus on objectives as the basis upon which the entire design process is based, and draw a lot from the work of Ralph Tyler. Those include the Wheeler, Kerr, and Taba models.

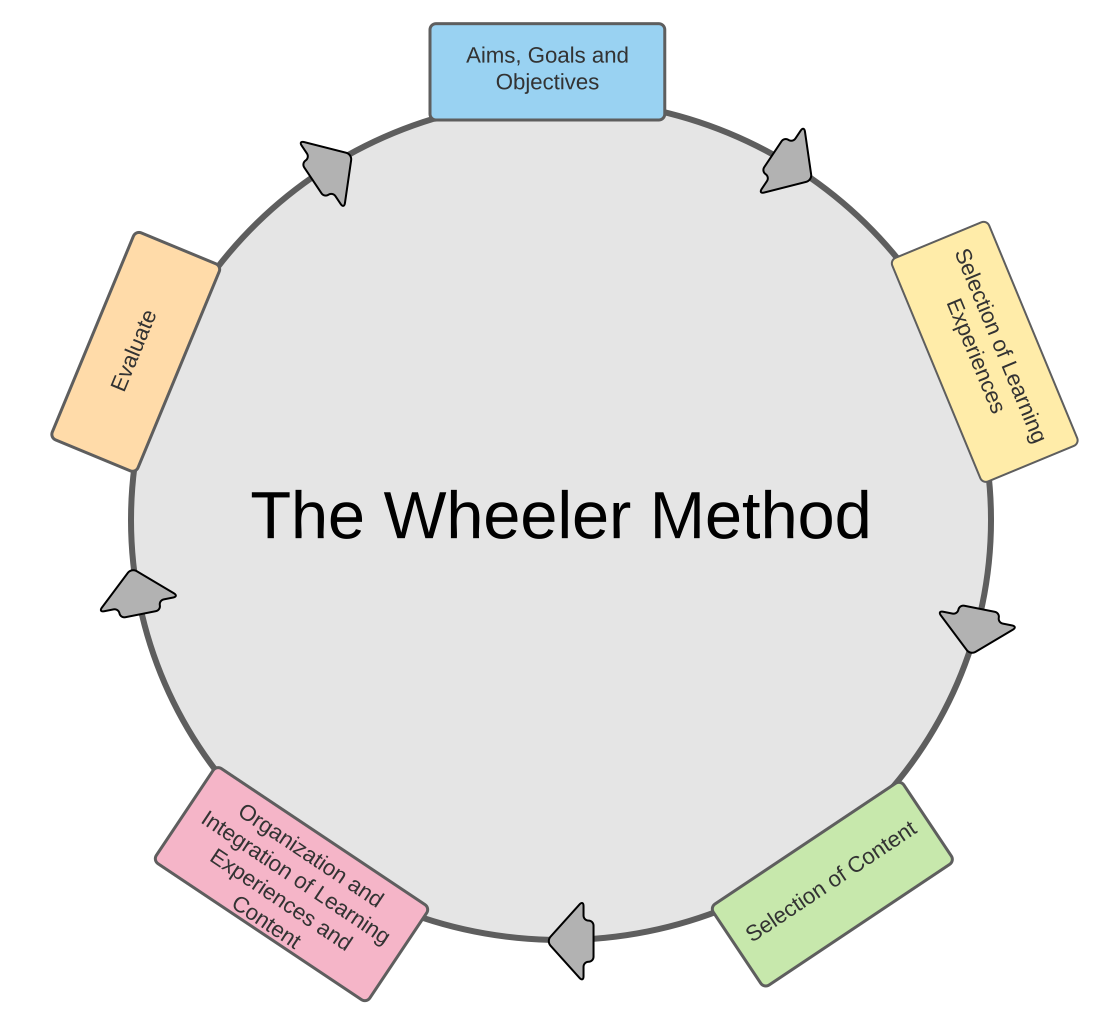

The Wheeler Model

D.K. Wheeler developed a cyclic model in reaction to criticism leveled at Ralph Tyler’s model. The latter was seen as being too simplistic and vertical. By being vertical, it did not recognize the relationship between various curriculum elements. His cyclic proposal was therefore aimed at highlighting the interrelatedness of the various curriculum elements. It also emphasizes the need to use feedback from evaluation in redefining the goals and objectives of the curriculum.

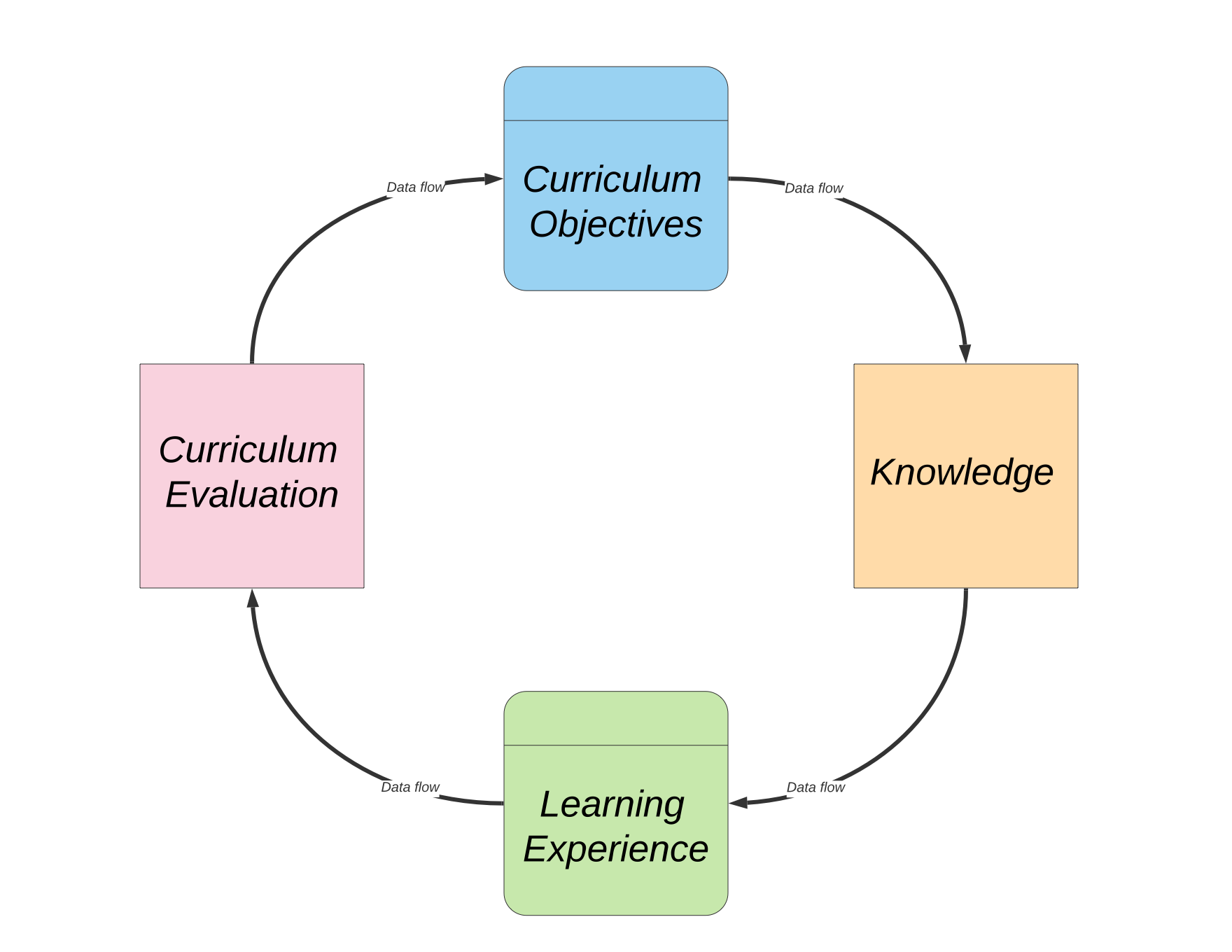

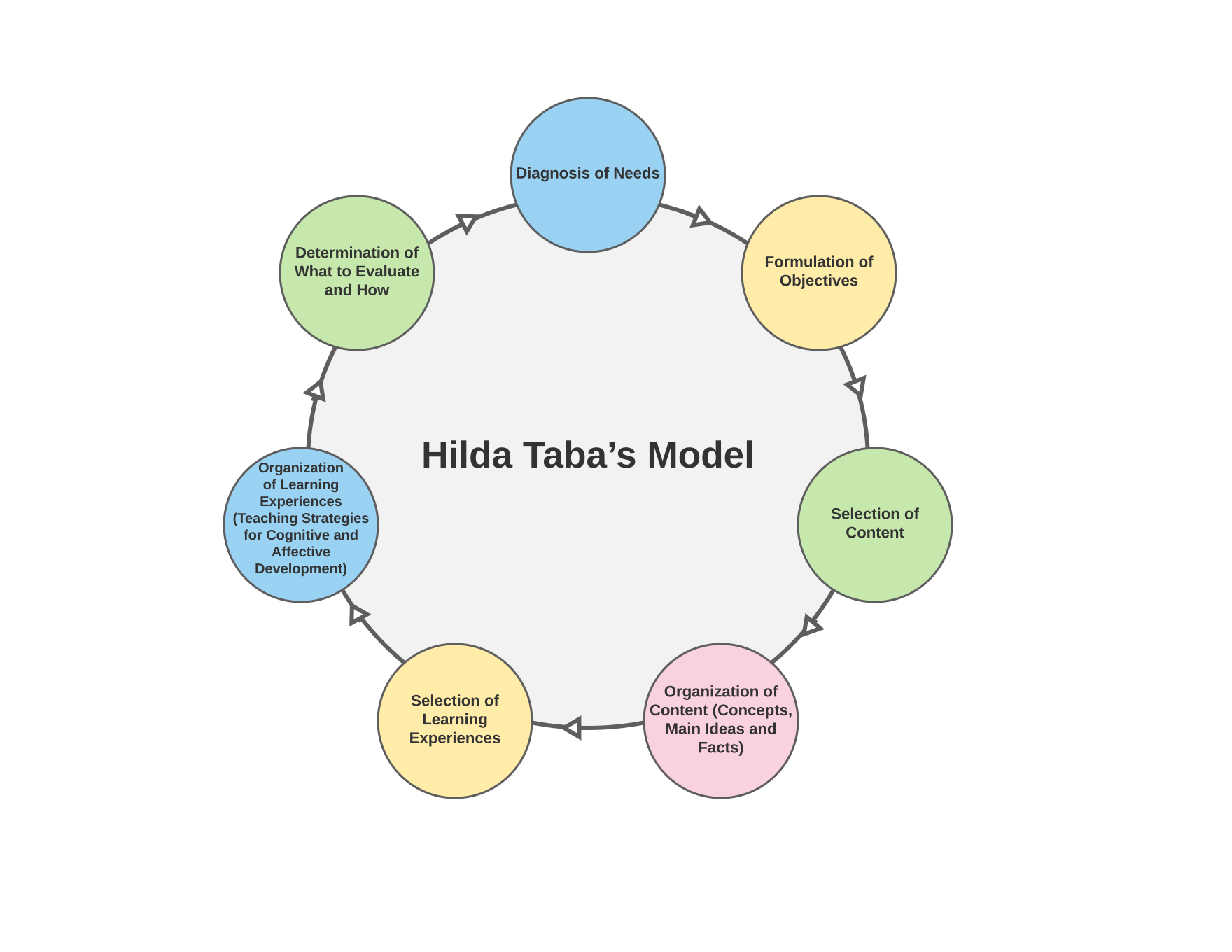

The Models of John Kerr and Hilda Taba

Other scholars who were also convinced of the ‘objectives’ approach to curriculum design were John Kerr and Hilda Taba. Their work is summarized in the simplified models presented in the graphic presentations that follow. Both of them emphasize the interrelatedness of the various curriculum elements.

John Kerr’s Model

John Kerr, a British Curriculum specialist in the 1960s, was particularly concerned with the following issues: objectives, knowledge, school learning experiences, and evaluation. This is reflected in the sketch below.

Kerr’s model is in many ways similar to that of Ralph Tyler and Wheeler. The difference is the emphasis on the interrelatedness of the various components in terms of the flow of the data between each component.

Hilda Taba’s Model

Hilda Taba was born in Europe and emigrated to the United States during a tumultuous time in history that had a great effect on her view of education. She was initially influenced by progressivists: John Dewey and Ralph Tyler, and one of her goals was to nurture the development of students and encourage them to actively participate in a democratic society. Taba’s model was inductive rather than deductive in nature, and it is characterized by being a continuous process.

Taba’s model emphasized concept development in elementary social studies curriculum and was used by teachers in her workshops. She was able to make connections between culture, politics, and social change as well as cognition, experience, and evaluation in curriculum development, particularly in the areas of teacher preparation and civic education. Taba’s work with teachers in communities around the United States and in Europe has provided a blueprint for curriculum development that continues to be used by curriculum developers today. To explore more information about Taba and her work, you may access Taba’s Bio.

Hilda Taba, on her part, was also influenced by Ralph Tyler. Her conceptual model follows. The interrelatedness of the curriculum elements from both models suggests the process is continuous.

Factors that Influence Curriculum Design

Several factors need to be taken into account when designing a curriculum. These include:

- teacher’s individual characteristics,

- application of technology,

- student’s cultural background and socio-economic status,

- interactions between teachers and students, and

- classroom management; among many other factors.

Insight 5.0

There is no “silver bullet” in designing curriculum. What is best for one classroom or one district may not work somewhere else. When setting up the process, using a combination of designs might work best.

ILA 5.0

If you were leading a curriculum committee, which model would you use for the curriculum development process?

Respond using the Hypothesis ILA Responses Group annotation tool. Choose the content area(s) and grade level(s), a specific model or a combination of models, and include rationale for your choices.

Summary

Curriculum design is central to the development of curriculum, and it can be done in several ways. Each design has advantages and disadvantages for both learners and teachers. Ralph Tyler included four questions that guided his curriculum design model. Tyler’s model influenced later curriculum designs by John Goodlad, D.K. Wheeler, John Kerr, Hilda Taba, and others. In the next chapter, we look at how curriculum is developed and its scope.